by Maurice Dunbar, El Camino Research Lodge

Jean II of the Valois Dynasty succeeded his father Philip VI in August of 1350. Most of the new King’s policies were mistaken, inadequate, or just disastrous.

His personal idea for improving the military was to found an order of chivalry modeled, like King Edward’s recently-founded Order of the Garter, on the Knights of the Round Table. Jean’s Order of the Star was intended to rival the Garter, revive French prestige, and weld the splintered loyalty of his nobles to the Valois monarchy.

The orders of chivalry, with all of their display of ritual and vows, were a way of trying to secure a loyal body of military support on which the sovereign could rely. That in fact was the symbolism of the Garter, a circlet to bind the Knight-Companions mutually, and all of them jointly to the King as head of the Order. First broached with much fanfare in 1344, the Order of the Garter was originally intended to include 300 proved knights, starting with the most worthy of the realm. When formally established five years later, it was reduced to an exclusive circle of 26, with St. George as patron and official robes of blue and gold. Significantly, the statutes provided that no member was to leave the King’s domain without his authority. The wearing of the Garter at the knee was further intended, in the words of the Order’s historian, “as a Caveat and Exhortation that the Knights should not cowardly betray the Valour.”

Since Jean II’s object was to be inclusive rather than exclusive, he made the Order of the Star open to 500 members. Established “In the honor of God, of our Lady and for the heightening of Chivalry and augmenting of honor,” the full Order was to assemble once a year in a ceremonial banquet hung with the blazons of all the members. Companions were to wear a white tunic, a red or white surcoat embroidered with a gold Star, a red hat, enamel ring of special design, black hose and gilded shoes. They were to display a red banner strewn with stars and embroidered with an image of Our Lady.

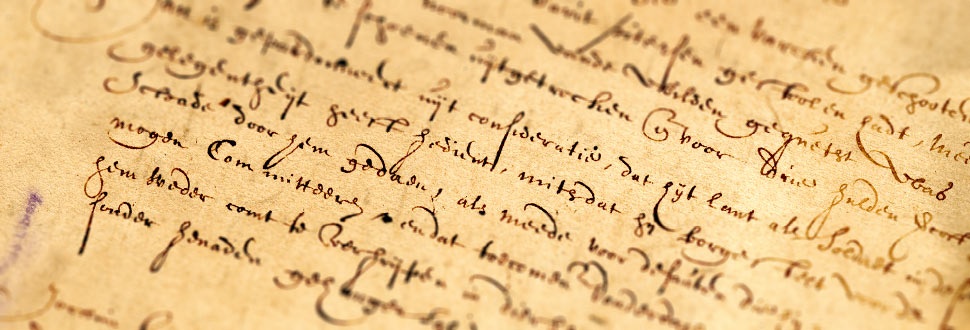

At the annual banquet, each would recite on oath “all the adventures that befell him in the year, both shameful and honorable,” and clerks would take down the recitals in a book. The Order would designate the three princess, three bannerets and three knights who during the year had done the most in arms of war, “for no deed of arms in peace shall be taken into account.” This meant no deed of private warfare as distinct from a war declared by the sovereign could be claimed as an adventure. Equally significant of the King’s intention was the reappearance of the oath not to withdraw, worded more sternly than in the ordinance and more explicitly than in the Order of the Garter. Companions of the Star were required to swear that they would never flee in battle more than four arpents [an arpent was about 150 yards] “but would rather die or be taken prisoner.”

With dazzling munificence, Jean II launched the Order of the Star at an opening ceremony on January 6, 1352. He donated all the robes and staged a magnificent banquet in a hall draped with tapestries and hangings of gold and velvet decorated with stars and fleurs-de-lis. After a solemn mass, the revels grew so rowdy that a gold chalice was smashed and some draperies stolen. While the knights caroused, the English seized the castle of Guines, whose absent captain was celebrating with his companions of the Star.

To their own undoing, the companions of the Star took seriously the oath not to flee from battle. In 1352, during the war in Brittany, a French force was caught in ambushed by the English. They could have fled and saved themselves, but they were bound by their oath not to retreat. They stood and fought until nearly all were killed or captured. This defeat left such a great hole in the Order of the Star, that it caused the ruin of that noble company.